Still Sunday, July 21:

The swarm (Apt E), with beautiful Elizabeth who let me see her when I inspected, was doing so well that I added a second box. They were doing everything they were supposed to do: drawing comb and building up their population. I took one frame of honey and pollen from them, slowly shaking off the bees as I walked it over to the queen castle. I placed it in the middle of the 3 queen castle sections.

The queen in the hive that cast the swarm (Apt. B) was laying eggs in the top super (5 boxes up) and the crew had not made a lot of honey, which pissed me off. There was nectar and no brood in the 3rd or 4th boxes, and there were some capped cells in the 2nd box up. The bottom box was just about empty, so I brought the box with brood down to the bottom, and did what I could to put babies and food where they belong. As instructed in class, I had added 2 supers after making the nuc; but they had not built up loads of honey the way they were supposed to do. As I tightened up the resources, I removed a box and gathered the 8 emptiest frames I could find to set them aside with it.

Caterina is on the right, with no stripes and an extra long abdomen.

Apt. C was looking almost mundane, it was so normal. This is the hive that used to have a nasty temperament and I had given it the new Russian queen. Her name is Caterina (because I figure a queen I paid for deserves a name). I saw Caterina and she was laying eggs like a good queen should, which made me very happy. I did some rearranging and swapped out some empty frames with ones that had some nectar from Apt. B. I was still looking for a third frame with honey and pollen for the queen castle, but there wasn’t anything that seemed just right. I closed up shop at this point, and set aside the box I had removed from Apt. B, filled with frames that I thought were empty. I decided to leave for a while and contemplate where to get that last frame of food, once I’d written my notes and thought about who had resources to spare.

Sounds like a good day of beekeeping, right?

Sounds like a good day of beekeeping, right?

I went inside and had a beer as I recorded what I had done and uploaded the pictures I had taken. It was when I looked at the pictures that I realized what was wrong with the queen castle: it was backwards. I had stenciled a different colored bee on each side, with a colored shape to match the entry and help the bees know which was their own. It wasn’t a critical distinction. Whether or not the stencil and entry match is no matter to the bees, as long as they know which opening is home. But I was determined that the effort I had put into making my queen castle beautiful would not be lost. All the bees had come from the same hive, so I could turn the whole top around without worrying if there were bees left in the bottom that ended up with a different group; they didn’t know they were different groups yet.

This meant that the time to turn the box around was now. Somehow, I was thinking that the whole castle was weak because each 3-frame section was weak, and I didn’t relight my smoker. But let’s be honest. I wasn’t thinking. One beer had made me stupid.

So off I went, in my shorts, with my gloves and veil on. As I began to lift the castle, I realized that it doesn’t have handles like a regular box. And the stand it’s on has 2 arched metal tubes that are just where I wanted to put my hands to lift the box. Rather than lift the thing holding it front-to-back, where there was no stand in the way, out of habit I began to lift the sides. The lift was awkward so I decided to reconsider the plan. As I put the box down, I began to feel stinging on my thigh. I looked down and saw a circle of bees, about 4 inches in diameter, crowding above my knee.

I don’t recall the exact sequence of events from here. There were more stings and I dropped the box; bees were everywhere and I ran. As I ran, I looked down at my legs, and each had a circle of bees, trying to sting my thighs. I flapped at my legs in all the places I was feeling stings, back and front, running towards the house and swinging my hands wildly. I gave my shorts a good shake and final swipe, and ran into the house. There were still bees on me so I pulled my pants off and brought them to the doorway. I could have just thrown them out onto the deck, but I didn’t want to hurt bees, so I tried to turn them right-side-out and shake off the bees, while remaining inside the house myself. As if this would matter with the door open. Geoff was standing in the kitchen, watching me. “Why are you doing that?”

I said, “I don’t know!” dropped my pants on the porch, and shut the door. Geoff was getting the last few bees with a cup and piece of paper, and I found one more in the kitchen. By then, the stings were starting to smart and I crushed her.

At the beginning of the season, I talked to a person in my club about Adolph’s meat tenderizer, which is what I had been using on my stings. Adolph’s contains an enzyme that reduces a person’s reaction, but it’s hard to get just the right water mix so the paste will stay in place. She uses baking soda toothpaste, which is always ready. Since getting that advice, I have been carrying baking soda toothpaste and band aids, as well as a homeopathic remedy called Apis Mellifica, in my bee toolbox. Using the paste and the remedy immediately after being stung has worked well to keep stings from getting too bad. But the toothpaste isn’t quite as good as meat tenderizer, so I still use it for bad stings.

I was a tad worried that I had just received more bee stings at once than I had probably gotten in my whole life. One knee had taken 6 stings in an area about the size of my fist. I put meat tenderizer on that area, with a big gauze pad taped over it to keep the paste from rubbing off. Geoff used toothpaste to get all the other spots he could see, because I couldn’t see them all. He covered each spot with a band aid to keep the paste in place. I had about 2 dozen bee stings on my thighs.

The miracle of the whole thing is that the bees did not sting me on the skin anywhere, which meant that none of the stingers got caught in me, which meant that none of the stings were bad. The bees attacked only the dark blue cloth of my pants, not my light-colored T-shirt or my legs or arms.

There’s a belief that bees attack dark colors, which is why bee suits are white. I have been told this is an old wives’ tale – that studies have been done, etc., that if there’s anything to it, it’s that bees react to a dramatic change in color, such as the line where a shirt and pants meet, or clothes and skin. All I know is the bees only attacked my dark blue pants and nowhere else. By the same token, that’s the area that was in front of them when somebody opened their house all of a sudden.

… and in case you’re wondering, as soon as everything was settled, after covering all the stings and before I took antihistamine , I restarted my smoker, put on my full suit with a pair of rubber boots tucked inside, and went back out there to put things to rights. The castle is now in place, with the front side front, and at least one of the sections had bees coming and going from it four days after my fiasco.

The stings never bothered me much. For two days, I took 2 Benedryl at night and Apis Mellifica all day, and I renewed the meat tenderizer and toothpaste every morning. I iced when they felt uncomfortable the first day, and aside from that, I really didn’t have a problem. I honestly cannot believe it.

P.S. Remember the “empty” box I removed from Apt. C? I set it aside while I was doing all my other tricks. When I came back, it was covered with bees and they wouldn’t get off; apparently there was still nectar in there that I could neither see nor smell. I tried various methods of covering it to keep them off and eventually had to smoke them off and cover it with a robbing cloth for a day.

It was a long day.

Today I moved Nuc 1 into the box that was my queen castle. Combined with a regular screened bottom, it’s a regular box. The next nuc I’ll add as soon as I’ve finished staining the box it will go in.

Today I moved Nuc 1 into the box that was my queen castle. Combined with a regular screened bottom, it’s a regular box. The next nuc I’ll add as soon as I’ve finished staining the box it will go in. I put IPM boards in all my hives last week, and the mite counts are very low. Given that everyone appears to be in good shape for food and population and not a lot of mites, I have decided not to treat for mites this fall. Last fall, I timed it wrong and probably didn’t do much good anyway because of the temperature when I treated, and my bees survived anyway. This season, I think the artificial swarms and all the splitting I have done has done a nice job breaking the mites’ brood cycle and knocking them down. I have wanted to figure out how to keep bees with a minimum of chemicals, and I since I have 5 strong hives (or will, provided that combining the two nucs works), I think I’ll take the risk.

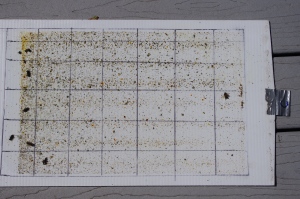

I put IPM boards in all my hives last week, and the mite counts are very low. Given that everyone appears to be in good shape for food and population and not a lot of mites, I have decided not to treat for mites this fall. Last fall, I timed it wrong and probably didn’t do much good anyway because of the temperature when I treated, and my bees survived anyway. This season, I think the artificial swarms and all the splitting I have done has done a nice job breaking the mites’ brood cycle and knocking them down. I have wanted to figure out how to keep bees with a minimum of chemicals, and I since I have 5 strong hives (or will, provided that combining the two nucs works), I think I’ll take the risk.